Dominguez Reflects on First Semester Fulbright Experience

When I was a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, one of the most influential voices for the kind of mathematics education research I wanted to do was Dr. Angela Valenzuela. In one graduate class that I took with her, she shared her experience as a Fulbright scholar in Guanajuato, Mexico. It is quite possible that her story, with all its ups and downs, may have contributed to my desire to apply to the Fulbright US Scholar Award. Other possible influences may have been my experiences in my own research projects, all of which I have envisioned as long-term collaborations with teachers and their multilingual, multiracial, and multicultural students in mathematics classrooms across the United States.

Prior to applying to Fulbright, I visited various public elementary schools in Latin

America, including Mexico, Colombia, and Chile. Having spent my formative years—primaria, secundaria, and a few years of universidad in Mexico—these visits reacquainted me with a familiar yet distant educational system. I spent

entire weeks in these international classrooms, often becoming an active agent in

the ongoing teaching of practicing and/or prospective teachers. In these experiences,

I learned that the neoliberal forces that have persistently taken a strong grip on

the US schools are just as strong in educational contexts abroad. At the same time,

the idea of fully embracing the role of a Fulbright Scholar as an ambassador engaged

in exchanging cultural and educational knowledge made me uncomfortable. How was I

supposed to take ownership of this role, when the idea of an exchange retained, at

least for me, an extractive desire, a strong resonance with capitalist language, as

in the exchange of goods and services.

Prior to applying to Fulbright, I visited various public elementary schools in Latin

America, including Mexico, Colombia, and Chile. Having spent my formative years—primaria, secundaria, and a few years of universidad in Mexico—these visits reacquainted me with a familiar yet distant educational system. I spent

entire weeks in these international classrooms, often becoming an active agent in

the ongoing teaching of practicing and/or prospective teachers. In these experiences,

I learned that the neoliberal forces that have persistently taken a strong grip on

the US schools are just as strong in educational contexts abroad. At the same time,

the idea of fully embracing the role of a Fulbright Scholar as an ambassador engaged

in exchanging cultural and educational knowledge made me uncomfortable. How was I

supposed to take ownership of this role, when the idea of an exchange retained, at

least for me, an extractive desire, a strong resonance with capitalist language, as

in the exchange of goods and services.

It took me a while to reinterpret my role as one consisting of encounters (and re-encounters)

with a once familiar educational system. With this re-envisioning of my role came

a clearer understanding of the purpose of generating new knowledge out of these encounters.

I am currently completing the third of my 9-month stay in Oaxaca and each day so far

has been filled with multiple encounters: with students, teachers, and school administrators;

city bus drivers, mountains, and hummingbirds; artists, cooks, and foods; new friends,

colors, smells, and tastes; dogs, donkeys, and insects; firecrackers, songs, and earthquakes.

Many of these encounters have helped me reconnect with my happy childhood in Mexico.

In my home, there were always rabbits, chickens, turkeys, ducks, a pair of geese,

some turtles now and then, dogs, and parakeets. It was a home filled with animal sounds

and the chattering voices of all of us around the kitchen table. I was always attracted

to art, color, and the beauty of animacy in my own world.

It took me a while to reinterpret my role as one consisting of encounters (and re-encounters)

with a once familiar educational system. With this re-envisioning of my role came

a clearer understanding of the purpose of generating new knowledge out of these encounters.

I am currently completing the third of my 9-month stay in Oaxaca and each day so far

has been filled with multiple encounters: with students, teachers, and school administrators;

city bus drivers, mountains, and hummingbirds; artists, cooks, and foods; new friends,

colors, smells, and tastes; dogs, donkeys, and insects; firecrackers, songs, and earthquakes.

Many of these encounters have helped me reconnect with my happy childhood in Mexico.

In my home, there were always rabbits, chickens, turkeys, ducks, a pair of geese,

some turtles now and then, dogs, and parakeets. It was a home filled with animal sounds

and the chattering voices of all of us around the kitchen table. I was always attracted

to art, color, and the beauty of animacy in my own world.

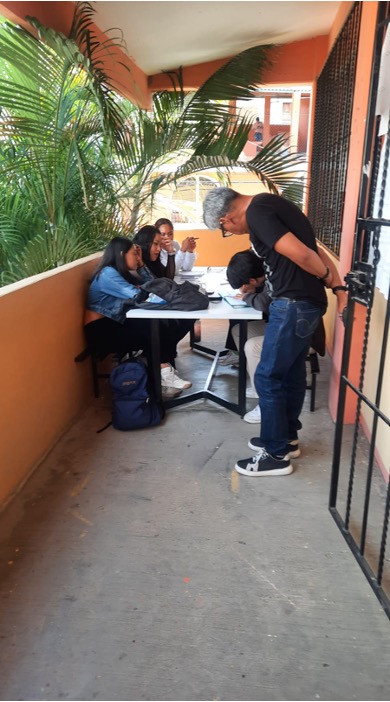

I came to Oaxaca to animate mathematical concepts with teachers and elementary school

students. As uncommon as this work is in Oaxacan schools, students have, without hesitation,

embraced it, demonstrating spontaneous appreciation—e.g., "Me gusta esta actividad!"—and respectful appropriation—e.g., "Tú eres mi maestro". Each morning, students welcome me with a big group hug.

One day, I asked them what each part of a two-digit number (e.g., 44) would be thinking

as we were counting and bagging pecans into tens. They suggested that the symbol "4"

on the left would be thinking: "I am ten bags of pecans" and the same symbol "4" but

on the right would be thinking: "I am only 4 pecans". One student stood up and asked

all of us: "¿Qué pasaría si juntamos los dos pensamientos?" (What would happen if

we joined the two thinkings?).

I came to Oaxaca to animate mathematical concepts with teachers and elementary school

students. As uncommon as this work is in Oaxacan schools, students have, without hesitation,

embraced it, demonstrating spontaneous appreciation—e.g., "Me gusta esta actividad!"—and respectful appropriation—e.g., "Tú eres mi maestro". Each morning, students welcome me with a big group hug.

One day, I asked them what each part of a two-digit number (e.g., 44) would be thinking

as we were counting and bagging pecans into tens. They suggested that the symbol "4"

on the left would be thinking: "I am ten bags of pecans" and the same symbol "4" but

on the right would be thinking: "I am only 4 pecans". One student stood up and asked

all of us: "¿Qué pasaría si juntamos los dos pensamientos?" (What would happen if

we joined the two thinkings?).

As for teachers, while these encounters have proven to be more challenging given the

systemic expectations they are subjected to, they too have enriched this project with

their creative ideas. Around Día de Muertos, teachers suggested using the altar de

muertos as a material/cultural/learning site to teach about how various valued objects

are placed on different levels or places as offerings for the departed ones. They

mentioned that this activity would promote the idea of value beyond material possessions.

Teachers have also engaged in critical reflection. In one of the first meetings with

them, I asked them to share at least one strength related to their mathematics teaching.

After a moment of hesitation, one said: "we have never thought about that question

because we are used to thinking not about our strengths but more about our weaknesses."

As for teachers, while these encounters have proven to be more challenging given the

systemic expectations they are subjected to, they too have enriched this project with

their creative ideas. Around Día de Muertos, teachers suggested using the altar de

muertos as a material/cultural/learning site to teach about how various valued objects

are placed on different levels or places as offerings for the departed ones. They

mentioned that this activity would promote the idea of value beyond material possessions.

Teachers have also engaged in critical reflection. In one of the first meetings with

them, I asked them to share at least one strength related to their mathematics teaching.

After a moment of hesitation, one said: "we have never thought about that question

because we are used to thinking not about our strengths but more about our weaknesses."

Teachers' desire to animate mathematical concepts is also palpable. In one initial session at two different schools, teachers created agentive encounters between their own bodies and diverse materials in the classrooms to express through coordinated movement the difference between space and place, a key difference to make sense of the concept of place value. Two teachers placed small pillows under their shirts to pretend pregnancies and with movement invited us to appreciate pregnancy as a beautiful example of the inseparability between space and place. Through these relational activities, teachers seem to be developing a collective voice to speak back to the neoliberal systems that insist on suffocating the possible in mathematics teaching and learning.

The remaining six months of my project will be informed by the wisdom, creativity,

and love of the possible shared by teachers and students in various schools in Oaxaca.

A beautiful idea that a group of teachers suggested was aprender haciendo, or learning

by doing. While the idea is not strange to me—as this is what I do when I work with students—I believe it needs to figure more prominently in my work with teachers. For a while,

I have been engaged in critical thinking about how the methodology and logistics of

my own research projects could be less invasive of teaching and learning spaces that,

in the end, I only visit. How can I envision a methodology that fits into a real practice

without adding intensity to the already intense practice of teachers? The wisdom in

this idea, generated by teachers in my project, will infuse the methodological and

analytical approach in the remaining months of my project.

The remaining six months of my project will be informed by the wisdom, creativity,

and love of the possible shared by teachers and students in various schools in Oaxaca.

A beautiful idea that a group of teachers suggested was aprender haciendo, or learning

by doing. While the idea is not strange to me—as this is what I do when I work with students—I believe it needs to figure more prominently in my work with teachers. For a while,

I have been engaged in critical thinking about how the methodology and logistics of

my own research projects could be less invasive of teaching and learning spaces that,

in the end, I only visit. How can I envision a methodology that fits into a real practice

without adding intensity to the already intense practice of teachers? The wisdom in

this idea, generated by teachers in my project, will infuse the methodological and

analytical approach in the remaining months of my project.

Written by

Higinio Dominguez

Most photos taken and submitted by Flor Luna, Higinio's mentor, for posting. She is

pictured in the fourth photo and seated in the middle. Many thanks for sharing these

fantastic photos!